Against Thermocolonialism, feat. Lizzie Wade

a conversation about making the seasons make sense

ADH: Last summer I wrote an essay coining a term for the persistent bias against hot places I’d observed everywhere from casual remarks by otherwise lovely Canadians to the reporting about Phoenix in various major news outlets. I called it “thermochauvinism.” The crux of the argument was that much of the global north/western world has been conditioned to see air conditioning and the other cooling technologies that make Arizona habitable during the summer as somehow shameful, and yet no one blinks at the gas heating and other infrastructure that make colder places habitable during the winter. In a warming world, we have to get over this bias.

Recently I chatted about this with the author and journalist Lizzie Wade, whose book APOCALPYSE: How Catastrophe Transformed Our World and Can Forge New Futures dropped earlier this year. We started musing about the ways thermochauvinism is rooted in the apocalyptic colonial project that she wrote about. We decided to capture some of our ideas along these lines in a conversation. Sign up for her newsletter, The Lizzie Wade Weekly, where she will too be posting this collaboration of ours.

So, hi Lizzie! To start, what’s your take on my general “thermochauvinism” thesis?

LW: Hi! Your thermochauvinism idea articulates something I’d noticed about the world but never thought to name or question, and now I’m seeing it everywhere – especially the bias against air conditioning and other cooling technologies. Many people in the global north see AC as an optional luxury, the people who don’t agree as weak and spoiled, and the places that need it for human thriving as doomed. I grew up in southern California with heating and central air, and while my family didn’t avoid either, I certainly thought that air conditioning was inherently more wasteful. We never had to adjust our home’s heating to avoid overloading the power grid, whereas that was and continues to be a frequent concern with air conditioning on the hottest days. I was surprised to learn from your essay that heating cold cities in the winter uses more energy than cooling hot cities in the summer. The fact that California’s power grid can’t handle everyone running their AC at the same time is a choice, not an inevitability.

I’m also thinking about another common narrative around AC, which is that spaces that are “overcooled” feel somehow unreal. Sometimes we welcome that unreality, like going to the movies on a hot day. Sometimes we gripe about it, like an office building where everyone has to wear a sweater no matter the temperature outside. But AC is associated with a sense of falseness, uncanniness, perhaps an uneasy sense of borrowed time in our era of climate crisis. I’ve felt that and I’m not sure it’s wrong — but your essay made me realize I’ve never thought of walking into a heated home or café on a cold day in those terms. There’s a sense that AC unnaturally separates us from our environment whereas heating provides a necessary and deeply human refuge within it. Gathering around the fire, etc. Again, I’m not sure either of those narratives is wrong, but trying to switch them around in my mind — cooling as refuge; heating as illusion — reveals how deep my cultural biases about them run.

I now live in Mexico City, where it’s normal to not have AC or heating. We’re in the mountains, above 7,000 feet, so the temperatures have historically been quite mild. Even now, when the hot months are getting hotter, it’s rare to go above the high 80s Fahrenheit. In the winter, it can dip close to freezing at night, but the days are usually sunny and warm. The houses aren’t typically insulated, however, so the indoors can be quite cold in December. There are days where I can wear a coat and gloves inside my apartment, and a sleeveless shirt outside.

But temperature is not really what defines seasons in Mexico City. What defines seasons is water. We have a rainy season in the middle of the year (it used to be April-September; now it starts closer to June or even July and it’s still going strong this October) and a dry season the rest of the time. I grew up with rainy and dry seasons in southern California, although there, winter was wet. Also, we called it “not having seasons,” because it didn’t fit this Northeastern US/European expectation that has been exported to and imposed on so much of the world. Saying Mexico City doesn’t have seasons would be ridiculous. But they don’t line up with the expectations of the people and places who colonized it — and who also drained the lake that used to cover much of what is now the city. Now there are catastrophic floods every single year.

ADH: The “gathering around the fire” image comes up a lot when I talk about this stuff. But looking at where Homo sapiens likely evolved and lived for most of our existence as a species, we’ve probably spent way more time gathering at the river or watering hole to cool off than around the fire to keep warm. See also Le Guin’s “Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction,” where she pokes at our habit of imagining a prehistory of cave men rather than river women. Just another little thermochauvinism living in all our heads. Maybe all this bias dates back to the ice age!

Anyway, good point about the electric grid — both that we underinvest in grid stability, and that our anxiety around AC might be tied to the narratives we’ve heard about heavy AC use contributing to blackouts. Interesting that we have this sense of how we collectively relate to our electrical infrastructure, whereas the main thing I think people know about gas heating infrastructure is to be careful where you dig and to beat it when you smell gas. Nobody worries they’ll blow out the gas network by turning their thermostat up to high. Though, I think attitudes about personal gas use were probably different during the energy crisis of the 70s. We pay attention to what’s scarce.

A couple years ago I lived for a while in northern Sweden, close to the Arctic Circle. Temperature-wise this was about as far from Phoenix as you can get, but still I noticed that people were used to explaining the unique rhythms of their seasons in much the same way that I’d done in AZ or that you’ve just done with Mexico City. They’d say, “Well, there isn’t quite a word for this in English, but here we have ‘spring-winter’ when the days get warmer but there’s still snow on the ground.” They were highly adapted to these rhythms, changing their lifestyles and social expectations with the seasons, and of course having lots of heating infrastructure to make the place habitable. Even though, in the grand scheme of history, modern heating isn’t that much older than AC, there was a naturalistic sense that these adaptations were the result of many decades or centuries of living in that environment and building culture around it. It’s the opposite of the “unreality” of living in a place where the environmental culturemaking has been erased by colonization — either because the people now living there feel like they are an extension of a society on the other side of the planet, or because the colonizers actively obliterated the pre-existing lifeways.

(Not that Sweden doesn’t have its own issues along these lines, particularly in the north, where some people feel like an extractive colony of southern Sweden. But I think the differences are more palpable outside of Europe.)

But yes, there’s something so weird about stringing Christmas lights on palm trees. Or seeing Santa in a big fur coat in Phoenix, where Christmas is a day on which I tend to push up the sleeves on my lightest sweater around noon. Compare that to the sense of rightness-in-place I felt this summer when I went on a solstice group bike ride, celebrating the beginning of the sun’s retreat by jumping into a bunch of Tempe fountains.

All this has got me thinking that maybe “thermochauvinism” is a symptom of a larger phenomenon. Might we call it “thermocolonialism”? The imposition of one society’s climatic norms and expectations (maybe “thermocultures,” to coin yet another term?) on a place with a different climate. Thoughts?

LW: Thermocolonialism — I like it! It makes me think of another essay you published recently, about how climate change (or rather, climate denial) could be a root cause of the post-truth, “reality is broken” moment we find ourselves in. Everyone knows something is deeply wrong with the climate — even people who don’t “believe” in climate change are experiencing its effects — and everyone also knows we’re not doing anything about it (or at least not even close to enough). This subconscious sense of unease and hypocrisy leads to denying the reality we know we can’t escape but also can’t face directly.

Colonialism has always run on an engine of reality denial, including by imposing one place’s thermoculture on others where it manifestly has no relevance. And yet we all have to pretend it makes sense, and the people who point out the absurdity are the ones who get shouted down as being ridiculous. In my book, I interpreted the modern world’s (or at least the modern West’s) felt sense that something is deeply wrong as the result of the apocalypse of colonialism. We know the world as it’s currently organized isn’t sustainable, in any sense of the word, but the colonial lie of inevitability has robbed us of our ability to imagine anything different, for our pasts as well as our futures. Which is why I think the first step toward building something better is simply doing the hard work of recognizing what is real, now: That our world is already post-apocalyptic. The monster we’re told is just over the horizon is in fact already here, and has been for centuries, disguised as progress and the way things have to be.

That disconnect between the thermoculture and the reality of a colonized place, whether it’s northern Sweden or southern California or Mexico City, is only growing more pronounced and absurd as climate change intensifies. It can certainly be a tragedy, but I wonder if it could also be a way out, a door swinging open to reveal a truth that is too big, and too inconvenient (h/t Al Gore), to see all of at once. Perhaps as part of a larger decolonial project, we can think about the right to our own thermocultures — to accurately describe the climate around us wherever we are, and to decide how to live in it without fantasy or imposition from somewhere else.

ADH: I really appreciate the concept that our post-apocalyptic-ness is at the root of the unease most everyone feels in modernity. My one hesitation is, was it ever thus? I’m thinking of the Abrahamic religions’ story of being kicked out of paradise, or the Hindu idea that we’ve been in the Kali Yuga, the age of conflict and sin, for 5,000 years. Many peoples across history have felt that something was wrong with the world — though not all, so perhaps we should look to those who did not build this sense of brokenness into their mythos.

For me this points to one of the big questions in thinking about either the future or the past: how much are events shaped by the structures that have always been there, and how much are they shaped by the new and novel? Is the course of history mostly driven by the emergence of new technologies or ideas, or are the latest inventions/platforms/gadgets/ideologies just a fresh coat of paint on the same old class hierarchy, the same old human instincts?

But climate change is definitely novel. For a lot of places, it will be destabilizing to the local thermoculture. One reason I started writing about this topic is because I think cities like Phoenix aren’t destined to be these abandoned ruins, but instead can offer lessons and blueprints that the rest of the world will need to learn from as the planet heats up. So yeah, a door swinging open. If we can shed thermocolonialism and figure out how to create lifeways that match our actual, existing weather, then maybe we can figure out how to adapt to changing climates. And vice versa!

Here we bump up against another tension, though, between the local and the planetary. Colonialism is clearly a bad way to try to do this, but I kind of do think we should be building planetary cultures and institutions that can better manage planetary-scale crises like climate change, pandemics, extinction, ecocide, et al. So how can we do that while also pursuing the decolonial project and encouraging the reassertion of local thermoculture?

LW: Such a hard question, especially since the existing examples of multi-country or planetary-scale cooperation I can think of protect and enshrine colonial and capitalist power relations (free trade agreements, military treaties, or even the UN, where the big guys get to be on the security council and smaller, often previously colonized countries rotate in). Key to my understanding of any decolonial project — and I’ll be the first to admit that I’m always learning how shallow and rudimentary that understanding is, and trying to deepen it — is the conscious and radical reversal of those power relations.

This isn’t planetary-scale, exactly, but it comes up with museum repatriation work quite a bit. Some institutions struggle to understand that it’s not enough for them, acting alone, to decide to “do the right thing” and repatriate artifacts or ancestors to the communities from which they were stolen. In order for repatriation to actually be restorative and reparative, those communities must be in charge of the process, the decisions, and the goals. Repatriation isn’t only about returning cultural objects or ancestral remains, although that’s important — it’s about recognizing the museum should never have been in charge of them in the first place and is now stepping back into a supporting or even subordinate role.

So in thinking about what planetary-wide cooperation and coordination should look like, perhaps the people to ask are those most negatively affected by climate change (and capitalism, and colonialism) so far. This isn’t a new idea — think of the moral clarity of the Marshall Islands representatives addressing COP — but it has yet to be meaningfully enacted on anything approaching a planetary scale. And I’m not sure it will be, at least as the world is currently structured. But if that structure were to collapse, as so many have before? Maybe then a lot more doors would swing open. Not all of them good, but not all of them bad either.

Ironically, climate change’s destabilization of local thermocultures underlines and amplifies how unsustainable colonialism’s homogenizing project has always been. Twisting environments, ecosystems, and cultures into something the rich and powerful think will make them the most comfortable does not work. It never has, and it never will. And yet we see them doubling down on this delusion all around us. It will probably be like that for a while longer, and the consequences will inevitably compound to make it longer still. I can’t stop them, and I have to live with it. But I don’t ever have to believe the lie I’ve been told that this is just how things are, and how they have to be. I know, with every rainy season flood of Mexico City’s phantom lakebed, that thermocolonialism can’t last forever. The places where it’s cracking are those that can show us the way to something new.

Preorder My Book

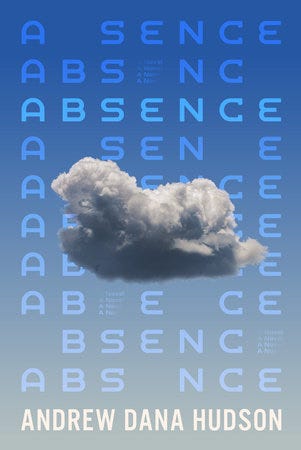

Absence: A Novel comes out May 5, 2026, from Soho Press. It’s a twisty cosmic mystery about a planetary crisis of human vanishing, and a woman who may or may not have the answers the world has been waiting for.

I was planning to talk more in depth about the book and reveal the cover next month, but then I noticed the cover was already percolating out to various bookstore websites. So, consider this a soft launch.

The important thing is that, yes, you can preorder it via Amazon, Bookshop.org, Barnes & Noble, and a number of other sites. You can also have your favorite local bookstore preorder it for you, which is often a good way to get it on more shelves around the country. However you choose to do it, your preorders are immensely appreciated.

More next month!

Art Tour: “Desert Heat Wave”

I saw another piece by this local artist, Aimee Ollinger, in one of the new exhibitions at the Mesa Contemporary. I had to track down the rest of her work and found myself delighted by the many elementally-roiling abstract landscapes. Also it turns out we have friends who already have a print of hers, so perhaps we’ll need to hop on that trend…