The Kids Are Not Okay (With Tech)

Lessons from Teaching Analog | Welcome to The Wackpot

1. How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love My Red Grading Pen

You may recall my last post-semester dispatch about teaching first-year composition in the age of the AI homework machine. This post got more traffic than anything else I’ve published on here, thanks to a timely share on Y Combinator’s Hacker News. I wrote about the banalities of trying to police AI writing and the struggles to get students to look up from their screens, resolving to ban device use from my classrooms and retvrn to using pen and paper.

So, how did it go? For the most part, well. In the final week of each semester, I always ask students for feedback on my course design. This time nearly all of them said they appreciated the break from their heavily tech-mediated lives and course loads. Even the student who had been most ornery and resistant to the device policy early in the semester had come around, said it helped him focus. Many reported that they found handwriting a better way to gather their thoughts and take memorable notes and voted to keep the handwritten assignments. They enjoyed how I used the whiteboard more and had them stare at boring slides less. All were appreciative of being given readings as printed handouts instead of webpages or pdfs.

I (and my comment section) had worried that working with pen and paper would be totally foreign to today’s freshmen, that I wouldn’t be able to parse their handwriting. Both fears were unfounded. Most of them had still been doing some pen and paper work in high school, and (perhaps because of the death of cursive) mostly their handwriting was very readable. Frankly my pen and paper skills were rustier than theirs, having spent the last twenty years doing all my writing via laptop. I was the one who at first found it a strange change to prep my lessons in a notebook rather than on slides, whose handwriting got sloppy when marking up their papers. But I acclimated, and soon I found grading a stack of papers a much swifter and less annoying task than churning through speedgrader on Canvas — situated as the latter activity is within the distraction-filled medium of the browser or the iPad.

There were some difficulties to my analog approach. Students mostly kept laptops away, but phone use was devilishly hard to suppress. I had a few students who sometimes openly scrolled Reels during class, and calling them out on it made me feel like I was teaching middle school, not college. AirPods sometimes stayed in if I didn’t bug them about it, and I could never tell if students had just forgotten they were in their ears or if they were surreptitiously listening to music or podcasts during class. I didn’t want to be a cop, but I occasionally had to play that role, in part because a lone device user was visibly distracting to my other students and in part because they were distracting to me as I tried to teach.

When students are allowed to have their laptops out, however, we can all maintain the fiction that they are at least partly taking notes or examining the reading or checking Canvas, as opposed to texting, shopping, doing homework for their other classes, or watching (e)sports. (Not that I have always been clean of such sins even as a grad student. I have a vivid memory from undergrad of a journalism prof scolding me and my friends for our incessant mid-class typing to each other on gchat.) Without the screen between us, it was way easier to tell when a student was disengaged, bored, spacing out. Some would yawn, fidget, stretch, check the clock, stare vacantly, even doze off. Students in the back whispered to each other; apparently one pen-and-paper skill that hasn’t endured is that of passing paper notes. That was all a new challenge for me, and occasionally made teaching demoralizing and enervating.

Such behavior varied a lot between my sections. My 1:30pm class was by default pretty alert and engaged, and being packed into a relatively small classroom made it harder for students to get away with breaching our collective social contract. By the time we got to my 4:30pm class, with its more sprawling classroom, both students and I were tired and ready to go home, and they had the room to use their phones under the tables without bumping each other’s elbows. These differences were more palpable without devices in the mix, but I was also able to attune to their moods and needs better, adapting my teaching strategies between sections, getting the evening students up and moving more often to put comments down on the whiteboard.

So: a lot of pedagogical exploration and growth. I still caught a bunch of students using AI on typewritten assignments, and there were others that I didn’t catch, merely suspected. But on the whole a good teaching experience, for all of us.

2. The Kids Are Not Okay (with Tech)

Probably the most striking part of this semester, however, was the theme of tech critique that ended up suffusing so many of our class conversations and so much of what my students wrote.

A solid chunk of my classes are devoted to discussion and analysis of various pieces of contemporary writing. For the first half of the course, I provide them with weekly “tabs” (a frame I borrowed from the excellent Today In Tabs newsletter, which admittedly makes less sense now that I’m usually printing these readings out). These include op-eds, longreads, book reviews, blog posts, podcasts, keynote videos, etc. Usually recent and topical, though for everyone’s sanity I try to avoid material that’s overtly partisan. I use these to give them examples of the kinds of writing they are being asked to do in class, to point out interesting and well-crafted sentences, and to expose them to the discourse that shapes contemporary culture.

In the second half of the course, these discussions continue, but I ask the students, in small groups, to provide the tabs, present on them, and lead the conversation. This semester nearly every article they chose was about the troubles and travails of our digitally mediated modern life.

There was the NYT podcast on AI’s impacts on education and the MIT study on ChatGPT-induced cognitive atrophy. There was this high schooler’s essay about struggling to get off her phone to pursue the hobbies she loved and this excellent New Yorker piece about the attention crisis. They talked about youth disengagement and screens in schools and maintaining friendships over text message and treating big tech like big tobacco. They debated if audiobooks count as reading and whether culture has come to a standstill. We spent most of one class period on our feet milling around after listening to a podcast about the dangers of “binge sitting.” That’s eleven out of twelve tabs we discussed across two sections. The single piece that didn’t clearly fit the theme was a Zadie Smith essay on essay writing, and I was pretty much the only one who really dug that.

Again, these were the articles they found and picked themselves to discuss with each other. The tabs I picked for them earlier in the semester occasionally touched on such topics but were just as often personal essays about friendship or telemarketing, gonzo journalism about dog shows, or chapters from this year’s ASU common read, Custodians of Wonder by Eliot Stein. I do think I primed the pump for them a bit with my own obvious interest in tech lash, but I don’t think their selections were all about pleasing teacher. This was what they wanted to talk about: social media and screentime and AI overuse. Several times I nudged the next group up to explore another topic, but usually they just found a different angle to address the same set of concerns. When it came time to pick one of the readings to write a response to for their final project, a huge portion of them chose to keep talking about tech.

These issues have come up before in previous semesters, but never with such overwhelming frequency and focus. I felt like they were constructing a syllabus for each other and me - Zoomer Tech Dilemmas 101. So it was fascinating to sit back and listen to them hash these questions out. These kids were mostly born the year the first iPhone dropped. They’ve never known a world without social media or smartphones. And yet they speak often about living through the sudden advent of “Technology” - by which they always mean digital devices and platforms; that an airplane or a nuclear power plant or an MRI machine might also be considered “technology” rarely crosses their mind. They aren’t always very articulate or clear-eyed about these circumstances they’ve grown up in, but they always have stuff to say about it.

That stuff is usually a mixture of frustration and defensiveness, along with anxiety about where Technology is going, a yearning for moderation, and a slight longing for the long-gone offline world. They’re scared about what this grand experiment we’ve run on them will mean for their adult prospects, but they also get annoyed by tech critics who don’t give due credit to the kinds of digital literacy they view themselves as having mastered. They see enshittification unfolding, but also they never really experienced the web before every inch was clogged with ads and paywalls and laced with dark patterns; as a result they can’t decide whether they should expect better. They agonize about doomscrolling on TikTok, but they also like that the endless flood of content means everyone has a chance to express themselves. They often say AI has a lot of valid uses, but don’t want students to be able to access chatbots until high school, maybe middle school at the earliest. They also unanimously claim they don’t think AI should be used to cheat, though I’ve found that a student expressing this opinion is no guarantee that they themselves won’t turn to AI cheating when they get stressed. They like the utility of social media, but wish it didn’t dominate their social lives. I’ve had a few students who apparently hoped that college would give them a chance to experience the kinds of friendships they’ve seen in, well, Friends, and then been disappointed to find that rushing a sorority or going to a frat party was still always mediated, still all about doing stuff on one’s phone.

There was a harsh undercurrent of recrimination in their discussions. Both of self and of others. What’s on your For You page, for instance, was the result of your choices most of all, not some mysterious algo, so don’t complain about the content you’re being fed. They have not yet learned how to be angry at big systems, so that energy curdles into guilt and shame. Sure, products like Instagram and ChatGPT are designed to be addictive by some of the smartest and best-funded people on the planet, but often students would say it’s still on the individual to not let themselves get sucked in. The Tyler,The Creator school of online governance is alive and well in Gen Z.

Probably the most moving sentiment I heard from them and read in their work was an acute concern for those generations even younger than themselves, Gen Alpha and so on. Zoomers see themselves as having gotten some unmediated childhood play, with core memories of just going outside and running around, climbing trees, etc. But they don’t see their younger siblings getting that same experience. They’re very concerned about iPad babies. Even a student who once bragged about regularly hitting twelve hours of screentime per day fretted about seeing his three-year-old cousin play Call of Duty on an unattended phone.

Of course when I hear this, I think, “Hey, that’s my line! Millennials are supposed to talk that way about you!” So perhaps every generation thinks of themselves as the last ones to have a foothold in the good, old, swept-away physical world. And like everything trends come in and out like the tide, the pendulum swings the other way, social manias are slowly moderated. Parents I know with babies and toddlers today are very keen not to let their kids be iPad babies. Many of my students reported that their schools had, in their senior year, implemented strict no-phone policies, including making students lock their phones in sealed pouches. (Enterprising teenagers bought magnetic keys online and unsealed their peers’ pouches for $5 a pop.) Data is piling up about how counterproductive school laptops and tablets are, and districts are starting to act accordingly. There’s every reason to think that we can and maybe even will mitigate and roll back some of the bad effects tech has had on young people over the last fifteen years.

But in the meantime it’s hard to shake the feeling that something has gone very amiss with this cohort now entering college, and that the students themselves are desperate to understand and articulate what that something is.

3. Teaching in the Great Literacy Crisis

Part of that something is: many of them can’t write. My first semester teaching comp a few years ago, I had a student who simply couldn’t put together grammatically coherent sentences and clear thoughts. I fretted a great deal about whether or not I should pass him. Now I’ve become numb to this common occurrence. Ever since, I’ve had more and more students whose writing is not just weak but close to non-functional, and this semester was the worst yet.

Rules of grammar that were so drilled into me as to become second nature by high school either were never taught to many of these students or somehow didn’t take. Many have a solid vocabulary, but don’t piece it together right. Often they know this, and are frustrated by it. I carved out part of one period toward the end of the semester to ask them what they wish we’d covered and blitz through answers, and most of the questions they had were about sentence structure and proper use of punctuation. When I did my course design feedback, several students said they wished we’d spent more time learning grammar.

This is not normal for first-year composition, even at a big access-focused university like ASU. Comp textbooks are all about understanding genres and rhetorical situations and types of argument, using and citing sources, being a part of academic discourse. In the rhetoric textbook I used this year, writing clear and correct sentences is covered in two slim chapters way at the back, more as a reference, an afterthought. If I could do it all over again, I would have begun this semester covering those chapters in detail, hoping to catch up some of the students who are writing at remedial levels.

Even some students who are gung-ho for school, who are engaged in the class, who are maybe even in the honors college, are struggling with basic writing in a way that they weren’t just a couple years ago.

Many other educators have been sounding the alarm about recent and sudden drops in student literacy, particularly reading comprehension and stamina. I’ve been seeing that too, though I got into this game too recently to know a world in which college students could fully absorb and understand 30+ pages of reading. Part of the reason why I do the tab discussions is to model for them the practice of reading an article, understanding its points, appreciating its strengths, and critiquing its weaknesses. This is not a skill they find easy when it comes to text. They struggle to hold in their mind the various movements of argument within, say a New Yorker essay. I can’t imagine what it’s like to try to get them to read full books.

AI makes recognizing and dealing with the writing/reading crisis infinitely worse. Some students compensate for their poor writing skills by turning to LLMs, which masks the true extent of the problem. In a confusing twist, this also makes teachers like me suspicious of any writing that is too clean and correct, and I think some students who do their own work know this and are introducing a few glaring errors to “humanize” their writing, just like their peers do to sneak AI-generated essays past graders. It’s a counterproductive and miserable spiral all around.

These LLM products are arriving at the perfect time to both paper over and exacerbate a growing literacy crisis. I don’t know how many of my students were never taught phonics and instead were told to learn to read using the long-debunked “three cueing” method — basically teaching as literacy the strategies that illiterate people use to cope and pretend understanding — but I know it’s not zero. I keep thinking about the student Clay Shirky wrote about in the Chronicle of Higher Ed who used AI to graduate high school with a 3.4 GPA while being completely unable to read, turning himself into a walking Chinese room thought experiment. The bigger the gap between what students are capable of and the demands of college or, for that matter, the professional world, the more they will want to and need to turn to AI to compensate. Such ever increasing dependence on fundamentally grotesque and untrustworthy systems is a recipe for precipitous social decline, not to mention the destruction of higher education and generational confusion, disappointment, and anger when the hallucinatory bubble pops.

In order to disincentivize AI use, I switched to “grading process over product.” I broke projects into more steps that students earned completion points for without being judged on quality. Final revisions were worth fewer points, and I tweaked my rubrics so fewer of those points came from categories like “clarity” or “polish.” In general I think this was a good practice, but it also gave me fewer opportunities to signal to individual students that they needed to up their grammar game, maybe seek help from the writing center or my office hours. Assuming those remedies are enough when one has gotten this far without some fundamentals in place.

And most of those students whose writing I don’t consider college level passed my class, just as they passed through high school. I don’t know if that’s good or bad for the students themselves in the long run; hopefully they improved and will keep improving, even if they are behind. But it doesn’t seem like it bodes well for society, and it’s unpleasant for me, personally, to feel like being an educator means being part of an assembly line of buck-passers without a clear buck-stopping mechanism.

Not that I’m passing everyone. This semester I’m failing more students than ever I have before, even though my class, in my opinion, has only gotten easier. Most of them just didn’t attend enough and, against my advice, didn’t withdraw before the deadline. Some didn’t turn in a bunch of assignments, despite many check-ins by email and face-to-face urging them to get something in. Sometimes these latter students were still coming to class regularly, participating and staying engaged. Sometimes they were totally fine writers. They just didn’t show up or didn’t do the work. There’s always been one or two, but this semester it’s a half dozen — a startling jump from the last couple years.

4. Welcome to the Wackpot...

The last few months, along with the articles my students found, my tabs were filling up with observations and takes about the decline of literacy, the struggles even elite institutions are having teaching the recent crops of college kids, and theories of the New American Dumbness. It’s grim out there!

So why is this happening now? Is it the phones? The brain rot content? The AI slop? The spoons-worth of microplastics in our brains? Is it the lingering impacts of the stultifying covid years and zoom school, or the multiple covid infections taking a hammer to our collective prefrontal cortex? Or, as I argued a few months ago, is it that the ever understood but rarely faced reality of unaddressed climate catastrophe has made millions give up, turn away, lose the plot? Is the cognitive decline trickling down from our insane, sundowning leaders, or trickling up from the content-entranced masses? Is it The Fascism?

In William Gibson’s time-communication novel The Peripheral, the high-tech hillbillies of the near future are separated from the higher-tech posh kleptocrats (and their servants) of the farther-future by a cataclysm called “The Jackpot.” We spend much of the book wondering what this disaster was that wiped out some 80% of the human population. A virus? An asteroid? A solar flare? A rogue AI? Nanotech gone mad?

The most memorable moment in the book is when Wilf explains to Flynne that, no, it wasn’t one single thing: it was a confluence. It was the climate getting worse and resistant disease spreading and tech acceleration and tremendous violence, all swirling together into an emergent, slow-moving global giga-disaster without clear beginning or end. On the other side, the decimated world is controlled by rich survivors, for whom the whole affair was both a bullet dodged and a dark Malthusian blessing. Probably we are already in The Jackpot now, Gibson suggests. Maybe we have been for 500 years.

That’s my theory about what’s happening to young people right now, too. It’s not one thing — it’s everything. It’s the covid years plus phones and social media plus ed grifters selling bunk curriculum plus No Child Left Behind plus the stupefying politics they’ve come of age around plus the AI slop now being shoved in their faces plus all the rest. Call it “The Wackpot”: an emergent generational crisis that may now coming to a head. Wack because most of the forces driving it are just so frustratingly dumb.

As worrisome as The Wackpot is, I had many students who were thoughtful and curious. They know something is wrong, and they’re intensely interested in figuring out a better way forward, even if they don’t yet have the frameworks to understand the systems that failed them.

And all these problems are solvable. We can return to working literacy pedagogy and get screens out of schools. We can pop the AI bubble and regulate social media as a public health concern. We can de-alienate and de-atomize. We can do right by the generations coming up, and offer educational remediation for the worst impacted.

I’ve been fiddling with a story that features an attention-span bootcamp. You sit and read War and Peace, and a drill instructor screams in your face if you check your phone. Maybe that’s dramatic, but I do think there will be demand for this kinda thing in the coming years. The changes I made to my teaching and classroom policies this semester feel like where everyone is headed, and more importantly seemed to be having a positive effect.

There’s an assumption that the young are rebellious and the old are complacent, but I don’t think that’s always true. When we are young, its very easy to accept the world, because we are powerless to change it and we don’t know how else it could be. When we come into adulthood, gain some measure of influence and mastery, and experience social change and change within our own lives, we have the opportunity to stop accepting, to develop analyses and push reforms. If enough other people come to similar conclusions, society can change quite rapidly and radically.

When I was eighteen, I don’t think I had a social critique as deeply felt as the one my students explored this semester. My politics were all over the place and didn’t start to coalesce until I sought to enter the workforce amid the 2008 financial crisis and the Great Recession. These kids are coming into their grievances and frustrations much earlier. I, for one, am interested to see what they make of the world, when soon they get the chance.

Book Updates and Blurbs

If you liked that long essay about finding hope amid decline, may I interest you in a long cosmic mystery novel about the same?

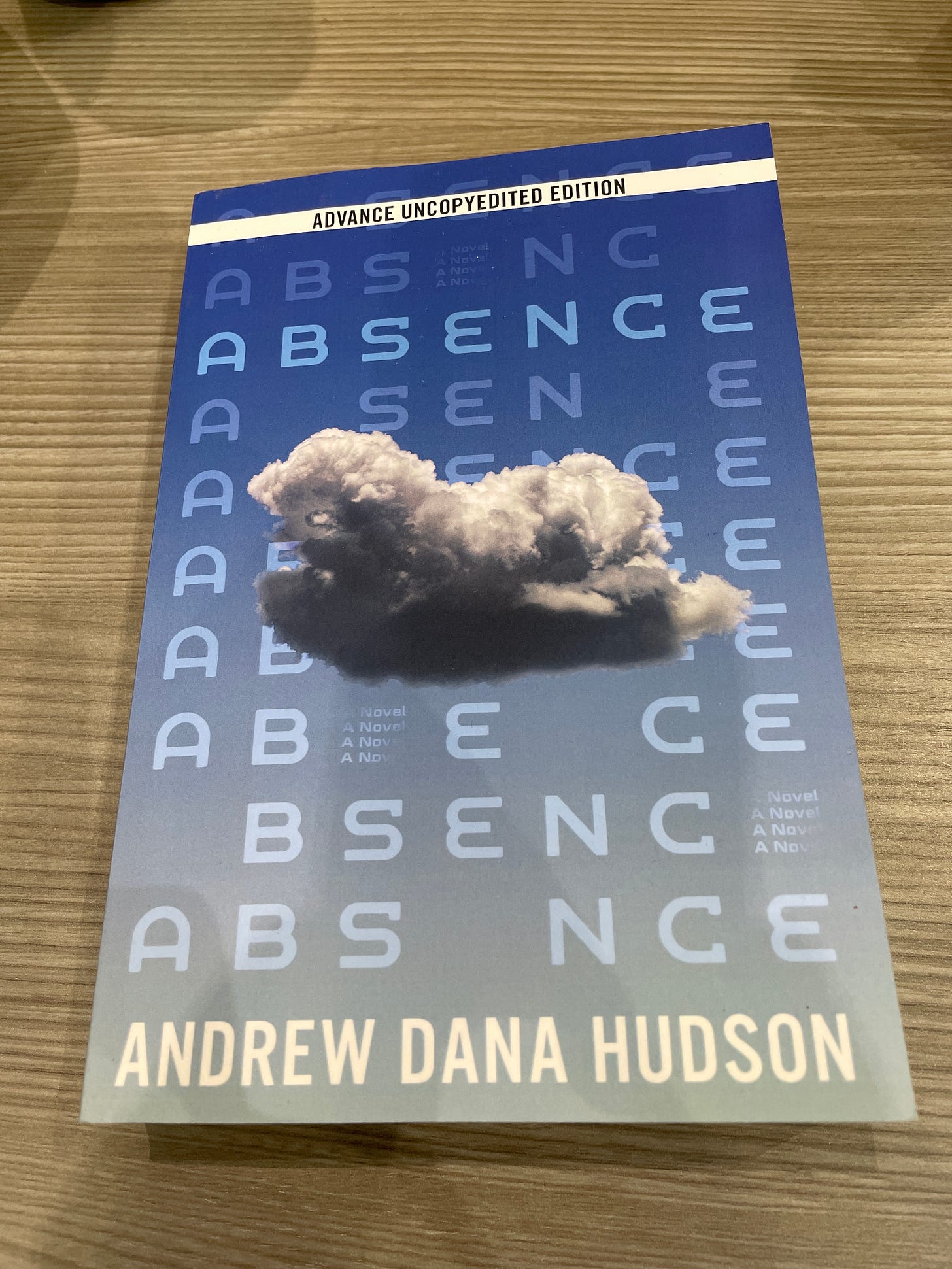

This week we are officially sending Absence to press! It was so wild to hold the ARC in my hands at last — an object in the world, rather than a document I’ve been fiddling with for year on my computer. It’s beautiful inside and out, and I’m so stoked to see the hardcover edition that drops in May.

Due to the holidays and a backup at the printer, we had a somewhat abbreviated ARC reading period. Nonetheless some fantastic authors took the time to read and blurb it, for which I am eternally grateful. Here’s what a few folks had to say:

“A wild, inventive, and extraordinarily prescient novel, Andrew Dana Hudson’s Absence unspools a moody detective yarn that quickly vaults sky-high, weighing humankind’s slow numbing against daily horrors and faith’s struggle against the impossible. And yet most impressively, within its nightmare of spontaneous gradual depopulation, much is made clear of our species’ capacity for hope. There simply aren’t enough books like it.”

—Jinwoo Chong, author of I Leave It Up to You and Flux

“A moving, enthralling story, set in a fully realized, beautifully examined world. Don’t let this one get away.”

—Sara Gran, author of the Claire DeWitt novels and The Book of the Most Precious Substance

“Absence is fascinating, shiningly clever, and thought-provoking. A thriller wrapped in dystopian almost-horror wrapped in a perfect enigma, anchored by a grounded and methodic agent named Harvey Ellis. Brilliant!”

—Manda Scott, Edgar-nominated bestselling author of No Good Deed

“In this engaging, closely observed and intensely humanistic story that reads like Mulder and Scully collecting the immanent evidence of the end of the world, Andrew Dana Hudson helps us see how the real path to a better tomorrow is through rediscovery of the connection and community we have lost.”

—Christopher Brown, author of Tropic of Kansas and A Natural History of Empty Lots

Absence comes out May 5, 2026. Preorder now!

Art Tour: Sleepers

Up top is a picture of Sarah Sze’s unique video installation Sleepers (2024), which I saw recently at the Denver Art Museum. We’d gone to Denver basically to see art, and this was a real highlight. One of the most entrancing projection works I’ve seen in years. It immediately made me think of the fractured attentions and thought processes that I see my students wrestling with, trying moment to coalesce into something clear and meaningful and whole. You can watch a short clip of it here.

Thank you very much for sharing your experience and insights!!!

I appreciate the thoughts, as always. It makes me wonder what the responsibility is for people who are literate, especially older ones.

Voting? Teaching? Modeling good behavior by writing engaging, thoughtful stuff?

I’ve been doing a lot of playwriting in Chicago for the past year, which has been great, but I struggle with the egos of some artists.

I wonder if writers have a duty to write currently? Or what other ways there are to make the world feel more nuanced and grounded. How we serve obligations to younger generations.