Political Dimensions of Solarpunk...Ten Years Later

We've spent a decade imagining better futures. Now what?

It’s been about 10 years since I first heard the word “solarpunk.” It came to me via Facebook feed, in the form of a link to Adam Flynn’s “Solarpunk: Notes Toward a Manifesto.” As a lapsed writer of SFF and one-time poli-sci major, this was a pretty irresistible title for me. So I clicked.

The piece still holds up (I’ve assigned it a couple times). It’s a brief and elegant medley of imagery, references, and sloganeering. It had stuff to say about pop culture, and politics, and the looming climate crisis. For me, the most exciting part was that it implied a science fiction that wasn’t ‘space manifest destiny’ (which I could tell wasn’t happening) or 'cyberpunk singularity’ (which I’d soured on living in the shadow of Silicon Valley) or ‘dystopia/apocalypse’ (which was oversaturated in the post-Hunger Games/Walking Dead media landscape of the teens). And that science fiction had a catchy name that seemed to open up bright vistas of previously clouded possibility.

I was living in the Bay Area at the time and realized that actually I kinda knew Adam. We had met a friend’s birthday escape room night in SF Japantown. So I sent him a message, and we got a beer and talked solarpunk, and pretty soon I started thinking about what I had to say on the topic.

The result was a longread-style essay on Medium titled “On the Political Dimensions of Solarpunk." Now, a decade later, this is one of the pieces of writing I’m most known for. It’s been read tens of thousands of times, cited in at least a dozen graduate theses, and translated into several languages. Here at around the 10 year mark of my involvement in solarpunk, I want to look back on this piece, talk about how it’s held up, how solarpunk has evolved, and what might be next.

(Obviously the following will make more sense if you read or at least skim the original essay, but feel free also to simply plow ahead.)

First, I want to acknowledge that writing “Dimensions” was personally transformative for me. Back in undergrad I’d done a lot of futures-minded opinion writing, but in the six years after, as I’d burned out of being a journalist and failed to fit in in tech, that muscle had atrophied. In 2015 I was doing communications for an innovation-focused healthcare nonprofit. I’d spent several years miserably deriving self-worth from the relationship I’d moved to California to pursue. To write my own ideas, for my own reasons, and have them find an audience — and then to have similar success with fiction a year later — permanently changed how I saw myself and what I wanted from life. It launched me into the careers I have since chosen for myself: author, sustainability researcher, critical futurist. Perhaps I would have eventually found my way to writing SFF no matter what, but I suspect it would have been a longer, harder road without this leap into the early discursive waters of solarpunk. For that, I am incredibly grateful.

What made “Dimensions” so influential at the time? Well, while these days longreads about solarpunk are thick on the ground (for years the joke was that more words had been written about the genre than of the genre), at the time it was one of a few serious treatments on the subject. It offered a definition of solarpunk that is still commonly referenced today: “a speculative movement to imagine and design a world of prosperity, peace, sustainability and beauty, achievable with what we have from where we are.” And it proposed a solarpunk slogan that struck a chord in the early days of techlash: “Move quietly and plant things.”

Those basic rhetorical hits were nestled in some 6700 words of sprawling sociopolitical commentary. To be honest I was dreading diving back to that slog for this retrospective, but rereading “Dimensions” today, my honest feeling is that it holds up extremely well. Better, in fact, than many of the takes and ideas I’ve had in the interim.

“Bloated malnourishment” has turned out to be a great descriptor of our contemporary consumer experience. The exploration of the implications of Bruce Sterling’s “old people, in big cities, afraid of the sky” has turned out to be pretty spot-on, though many old people have thus far proven more afraid of foreigners, or of those big cities, than the climate monsters actually coming for their necks. The solarpunk “fail states” (smogpunk, hazmat-punk, sprawlpunk, Gibson’s Jackpot) feel like four horsemen now stalking across our unfolding planetary catastrophe.

The essay is clear eyed about a number of tough questions, from the long term decline of the state under capitalism, to the limitations of mass movements, to the need for a paced, long-term, community-oriented outlook on climate work. Clearer-eyed than I myself have often been over the years. And it does a good job of pointing to distinctly solarpunk responses to these questions, which still feel relevant and productive, if perhaps a little pat.

“Easy for you to say!” I found myself scowling at 2015-me. It’s one thing to know that building a better world amidst disaster is going to be a difficult, agonizing process requiring endless patience, compassion, and focus. It’s another to try to work through those difficulties, enduring the agonies, and stay patient, compassionate, and focused.

But this is why I’ve always been drawn to speculative literature as a lens for making sense of the world: the high temporal vantage point allows for self-honesty and inconvenient insight.

When “Dimensions” came out, probably only a few hundred people in the world had ever thought particularly hard about solarpunk, and most of them were on Tumblr. My essay was addressed to that cohort: earnest, online, clever, somewhat younger than me. I wanted to pass on the grab bag of political wisdom I’d acquired during my first decade of adulthood, gathered autodidactically through reading thinkers like David Graeber, following Sterling’s WIRED blog and other aggregators of globalization signals, and hanging around Occupy protests. In doing so, I hoped to nudge the collective imagination I saw at work on Tumblr toward a pragmatic engagement with reality, rather than simply too-good-to-be-true utopian world building.

This is still a real tension in solarpunk. Plenty of solarpunk works feel fully utopian, or at least post- some grand ’transition’ in which the messy matters of power and political struggle were resolved. Some aren’t even set on Earth, or feature various magical technologies that obviate the need for sustainability considerations. I still vigorously believe solarpunk works best as a vision of the fight for a better, greener Earth. But I’ve also become copacetic about it, in part because I think “Dimensions” makes my case on the matter, and I’m happy to leave it there. Solarpunk works fine as a big tent, and lots of people clearly yearn for cozy, utopian alternatives to our conflict-ridden reality.

But the appeal of this escapist impulse within solarpunk highlights the ways “Dimensions” did miss some of the predictive mark. For a year and change later, Trump would lurch into the White House, kicking off a decade+ of political incoherence from all sides, which has trickled out and been replicated across much of the world. In amid that relentless storm of shit, cozy utopias become both more appealing and, in some ways, more radical.

Honestly, the fact that “Dimensions” doesn’t mention, even by omission, US-American presidential politics is one of the best things about it. Hard to imagine such an extensive political treatise doing that today. The result is a set of structural analyses that feel broadly correct, but that lack fidelity. Yes, we are indeed sliding toward a “global oligarchy of the mega-rich,” based on destroying the middle class and dismantling the nation-state. Boy are we ever! But the way that’s happening, with maximum stupidity and spectacle, makes that process feel much more contingent, built out of historical particulars, coin flips that could go either way. (Possibly this feeling is just copium, hard to say.) These particulars matter a great deal when trying to make sense of the present moment and move into the future.

In 2015, I felt like neoliberalism had poured molasses over the levers of socio-economic change. I’d assumed we were plodding toward a second Clinton era defined by a combination of managed decline and mild progress that was mostly palpable as reduced expectations. I saw solarpunk as an antidote to that situation’s characteristic lack of political imagination.

But Trump, Brexit, COVID, Ukraine, and the many other black swans, ‘populist’ turns, and destabilized geopolitical swerves since 2015 have demonstrated that neoliberal technocracy does not actually have its hands firmly on the steering wheel of history. Which means that, for better or worse (right now worse), much more political change is possible than I had previously thought. This changes how we strategically relate to politics.

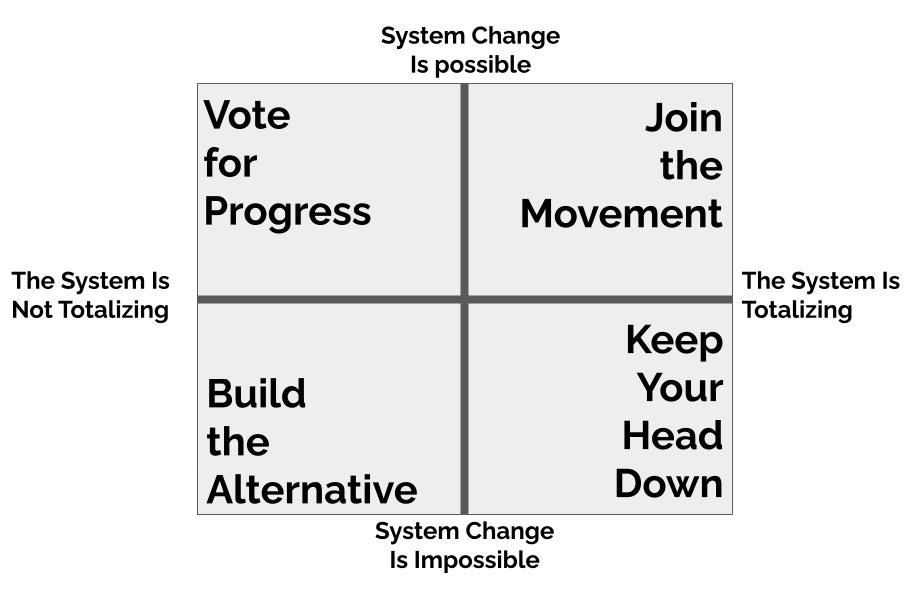

In 2019, for a zine essay, I explained my personal 2017-ish evolution from Graeberian anarchist to DSA-style socialist using the following diagram:

Basically, your guess as to the power and intractability of the present hegemonic system determines what you think you can do about it, which in turn determines, as much as your values, your actual active ideology. Today that system is capitalism, but 500 years ago you could have applied this quadrant to monarchy or the Catholic Church.

“Dimensions” nestles solarpunk firmly in Build the Alternative:

In light of their power, overthrowing the mega-rich is a dicey project, and one perhaps left to a different kind of political aesthetic. Instead solarpunk can challenge the capitalist status quo by nurturing alternative economic arrangements at a community and network level. Encourage resiliency that insulates towns and neighborhoods from economic shocks. Forge mutual aid pacts that protect members from fiscal predation. If we can prove that we don’t need them or their money, the chokehold of the plutocracy will loosen.

But that strategy only makes sense if you think there is a chokehold, that political upheaval is not imminent. The advent of populism in the late teens changed that calculation for many. If Trump could get elected, anything could happen, and might!

So people who might have previously been drawn to solarpunk Alternative Building strategies, like mutual aid and guerrilla infrastructure projects, instead flocked to the organized left, hoping to make a play for the levers of power. (I was one of them.) And indeed, in those heady years after 2016, DSA chapters and other such spaces were rife with debates about the role of such activities——versus, say, electoral campaigning or labor organizing——in the broader left political project.

Along with this swing in apparent political possibilities came increased ambitions for policy programs——both because Trump revealed how close to crisis we were (and now we are no longer merely close), and because the limp neoliberal reforms of the Clinton/Obama eras were blamed for Trump’s rise. This meant, in the US anyway, that universalist policy ideas like Medicare for All, a basic income, or a jobs guarantee gained new attention. As did what would soon become, for a while at least, the premier hope for addressing the climate crisis: the Green New Deal.

The Green New Deal (and its accompanying propaganda) had a lot in common with solarpunk. Both embraced renewable energy and rail infrastructure as beautiful parts of the landscape. Both were full of lush, green, city scenes packed with bicycles and diverse, happy peoples. Both offered meaningful work on material reality as a way out of economic and social alienation. And in 2023, AOC, one of the Green New Deal’s main champions in Congress, endorsed solarpunk on an Instragram livestream.

But over the years I occasionally argued that solarpunk was not quite the aesthetic of the GND. To me, the best solarpunk is countercultural (that’s what the “punk” means), exploring what a visionary, dissident minority might do when they get their hands on the technology of sustainability, like cheap solar panels, innovating new life ways that prefigure a better world. As Gibson said, “the street finds its own uses for things.”

The GND, on the other hand, needed to be majoritarian, a program that could turn a huge portion of the working class toward enacting the climate transition. It needed to be about millions of regular people going to work on projects that would save the planet, and about universal economic reforms that would provide the masses with greater security in an increasingly unstable climate. The ‘New Deal’ part of the name harkened back to a previous era of big infrastructure carried out by proactive public servants——the state rising the challenge, rather than leaving cracks that clever punks could fill. All this seemed to me a different vibe than crusty, nonconformist, countercultural solarpunk.

That said, my view on this was somewhat changed on this by Cory Doctorow’s novel The Lost Cause. In that book, the Green New Deal has been passed, but still the novel is full of solarpunks of various stripes. They are the ones pioneering the lifestyles of the future, leading caravans of climate refugees, leaping into action when disasters strike, defending the GND from maga reactionaries, and generally pushing for the GND to actually be enacted with vision and ambition. They are out there asking forgiveness not permission to carry out the transition that the broader society has agreed to, but may not always take initiative on. An activist minority, not exactly dissident, but definitely radical. A vanguard.

The point is, the political dimensions of solarpunk are not necessarily static. They looked one way in 2015, and looked somewhat different by 2018, because the political situation around them changed. In 2020 I noticed an uptick of attention flowing to my “Dimensions” essay, as the strain of the pandemic brought issues of state decline into sharper relief. In that moment, mutual aid to fill in the gaps in state capacity again seemed like a viable and valuable strategy for social change, and there were a great many of those efforts that popped up everywhere——though I think these proved hard to sustain as life for many become more and more online, yet further removed from the engagement with material reality that distinguishes solarpunk from cyberpunk. Then under Biden we got the IRA, and for a brief time it seemed like maybe there was room for entrepreneurial solarpunks to soak up some of that money and put it towards more radical projects. And now, with fascism on the march and the American administrative state in tatters, solarpunk needs to comport itself into the larger struggle to fight and resist authoritarianism and oligarchy, while also working to sustain communities through the bad times and conceiving of the new social compact that can come after.

(All of this, of course, is speaking of mostly of the American context, and solarpunk has always been a global phenomenon, with lots of activity in Europe, in Brazil, in Australia, in Canada, all over. In many of those places our recent dive into political iniquity has actually shifted the political winds in the opposite direction.)

Again, this present situation of decline and hostility from the state is not that different than the future context for solarpunk struggle “Dimensions” imagined. I see two major distinctions, challenges that don’t feel fully grasped in “Dimensions.” First, in the US at least, the Trumpian right is an increasingly irrational, destructive, and powerful opponent of a better world. Not only do they resist sustainability, they are throttling in the opposite direction. They don’t just refuse to believe science, they want to destroy science. They aren’t just blocking policy reforms but actively pushing against the economics that have tilted to favor renewables. All this feels like it could last for decades or change in an instant.

Second, and relatedly, the information environment is much worse today than I predicted in 2015. (On a recent call Jay called it “a decade defined by an extremely toxic interpersonal environment for ideas.”) Social media, under the auspices of oligarch platform-rule, has turned out to be both addictive and socially/intellectually corrosive in the extreme, particularly for elites and various civil society/courtier-types (reporters, pundits, activists, etc.). Journalism is either in tatters, captured by billionaires and private equity, or strung out on discourse-clicks. The web as a repository of knowledge is crumbling. For various reasons (particularly, I think, the ‘inconvenient truth’ of the climate crisis), our ability to accurately perceive and learn about reality has atrophied, or been deliberately sabotaged. The trauma and dislocation of the pandemic massively accelerated this process, and now the genAI iconoclasm/infoclasm is accelerating it further. As Neal Stephenson recently put it, one of our big contemporary problems, along with too much carbon in the atmosphere, is that we simply can’t agree on what’s true.

There’s a lot more we can say about both of these challenges, but in short they make doing solarpunk both harder and more necessary. The more cyberpunk the world gets, the more useful solarpunks become. The more material reality is buried under layers of digital abstraction, the better it feels to actually get your hands dirty.

Despite the challenges——or perhaps because of them——solarpunk has, on balance, been a tremendously successful “memetic engine.” In 2015 solarpunk was a hypothetical literary genre without any actual literature in it. Now there are hundreds of short stories, dozens of anthologies and magazines, a handful of prominent novels, and many more eclectic works that are explicitly called or marketed as “solarpunk.” (Not to mention all the solarpunk Content on Youtube, Reddit, Instagram, etc.) Plus, an order of magnitude more works have clearly been influenced by solarpunk sensibilities without adopting the label.

(Sometimes you see people trying to iterate further on the -punk genre, insisting that their sustainability-minded fiction/aesthetic is actually “lunarpunk” or “soilpunk” or “hopepunk.” I don’t think most of these sub-subgenres are actually A Thing, but who cares? The point of genre terms is to let people heuristically access new swaths of possibility space. If a new or niche -punk does that, let a thousand flowers bloom.)

Much of this literary work has been cultivated very deliberately through short story contests and anthology calls. People didn’t just spontaneously start writing solarpunk; often they started because someone asked them to. This has been a core mechanism of the memetic engine. One of the first bits of solarpunk punditry was Adam Flynn’s “On the Need for New Futures” way back in 2012. This sentiment has since been echoed by many, many institutions and publications. Which has in turn cultivated and enhanced solarpunk’s open, pluralistic, and polyphonic nature.

In the realm of politics, it’s a little murkier. On the one hand, there’s that AOC shout out. Ten years from Tumblr posts to literally the halls of power, endorsed by one of the most important political figures in the country (nothing but respect for MY president)——that’s a pretty good outcome for a cultural project that had, to start, a dozen or so dedicated advocates.

On the other, you have, for instance, Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson’s book Abundance (see various discourse) using solarpunk vibes to try to set the next agenda for the US Democratic Party. The central Abundist pitch is to call for various reforms that could allow us to build more housing, renewable energy, transit, et al: “Abundance reorients politics around a fresh provocation: Can we solve our problems with supply?” Off the bat, that doesn’t sound so bad. I myself have made a variation on this argument since at least 2018:

Let’s give ourselves one out, one advantage, something we can work with, right? A tool we can crack into these problems with. Abundant solar power, that’s a good one. One because that’s what we’ll need to capture and dispose of the 500 gigatons or so of carbon waste we’ve dumped into the atmosphere. And two because abundance is a paradigm that breaks people out of the zero-sum thinking that makes poverty and deprivation seem unavoidable.

So in some ways, we can interpret the presence of the Abundists faction among the center-left as a real win for solarpunk. Isn’t this kinda how politics should work? You make a proposal that at first seems radical, but if you make it consistently enough and convincingly enough, your ideas will trickle through the political spectrum until even moderates and conservatives find a version of your proposal palatable and sensible. Overton Window = moved. You may not get all you were asking for, but you get some, and that’s a win, and you keep fighting from there to get more. We didn’t get the GND, but we got the IRA, and (for a little while) that was a generational triumph for the climate movement.

But it’s also very easy to view the Abundist movement as an attempt to co-opt and strip away all that makes solarpunk (and the GND!) truly transformative. Some have called it a Trojan Horse to advance neoliberal de-regulation under the banner of the green transition. Matt Bruenig argued that it’s a play to offer “the most progressive-sounding agenda that does not involve significant welfare expansions, tax increases, unionization, or public ownership.”

And certainly, many would love to just build the garden-roofed ecotopia without all the messy class struggle, the delicate balancing of various environmental and community concerns (red tape, ugh!), the slow growing of real grassroots resilience and power? Solarpunk subreddits, Facebook groups, and other image-forward spaces have long fielded debates about whether solarpunk *had* to be anti-capitalist. This is one of the hazards of being an aesthetic as well as an ideology.

My take is that we can be for abundance, but to solarpunk the low hanging fruit of meeting-everyone’s-needs-and-then-some is seizing the vast hoards of wealth and real estate controlled by the ultra-rich. Some of the earliest solarpunk stories featured Occupy-style movements taking over empty penthouses and corporate offices and using them to house and care for refugees and the unhoused. Or else solarpunk imagines building amazing things outside the market economy: permaculture-subsisting punks salvaging roller coaster steel from flooded theme parks to create magnificent, multi-use art structures; not private developers throwing up endless, shoddy, gentrifying condos, many of which will be turned into AirBNBs or sit vacant as stores of investment capital, not human beings. Are such anarchist dreams always realistic? Of course not. They’re aspirational.

The Abundists are just the latest in a series of moments in which solarpunk has had to confront the contradictions of getting more mainstream. The “Dear Alice” Chobani ad, for instance, prompted much gnashing of teeth about corporate co-option of solarpunk aesthetics. (FWIW, I think it’s actually really powerful that some firms like Chobani, Chipotle, or IKEA are taking big swings toward sustainability, not because of pressure from activists but because they are voluntarily choosing to align with the solarpunk vision/meme.) Or genAI imagery is, justifiably, much maligned in solarpunk circles, and yet I’ve met people who found out about solarpunk through Midjourney forums and were inspired to move into careers in solar.

At the same time, solarpunk has absorbed a bunch of positive influences that weren’t so much a part of the conversation a decade ago. Actually reading Indigenous ecologists and philosophers has helped solarpunks ease out of the Western mindset and has given solarpunk historical examples of sustainability to emulate. Library Socialism has emerged as one of solarpunk’s most compelling economic concepts. Planetarity has given solarpunk a way to think through bigger scales. And as a literary movement, solarpunk has grown up alongside a broader push for more inclusive and diverse speculative fiction, so that more peoples and cultures can see themselves represented in futures and fantasies.

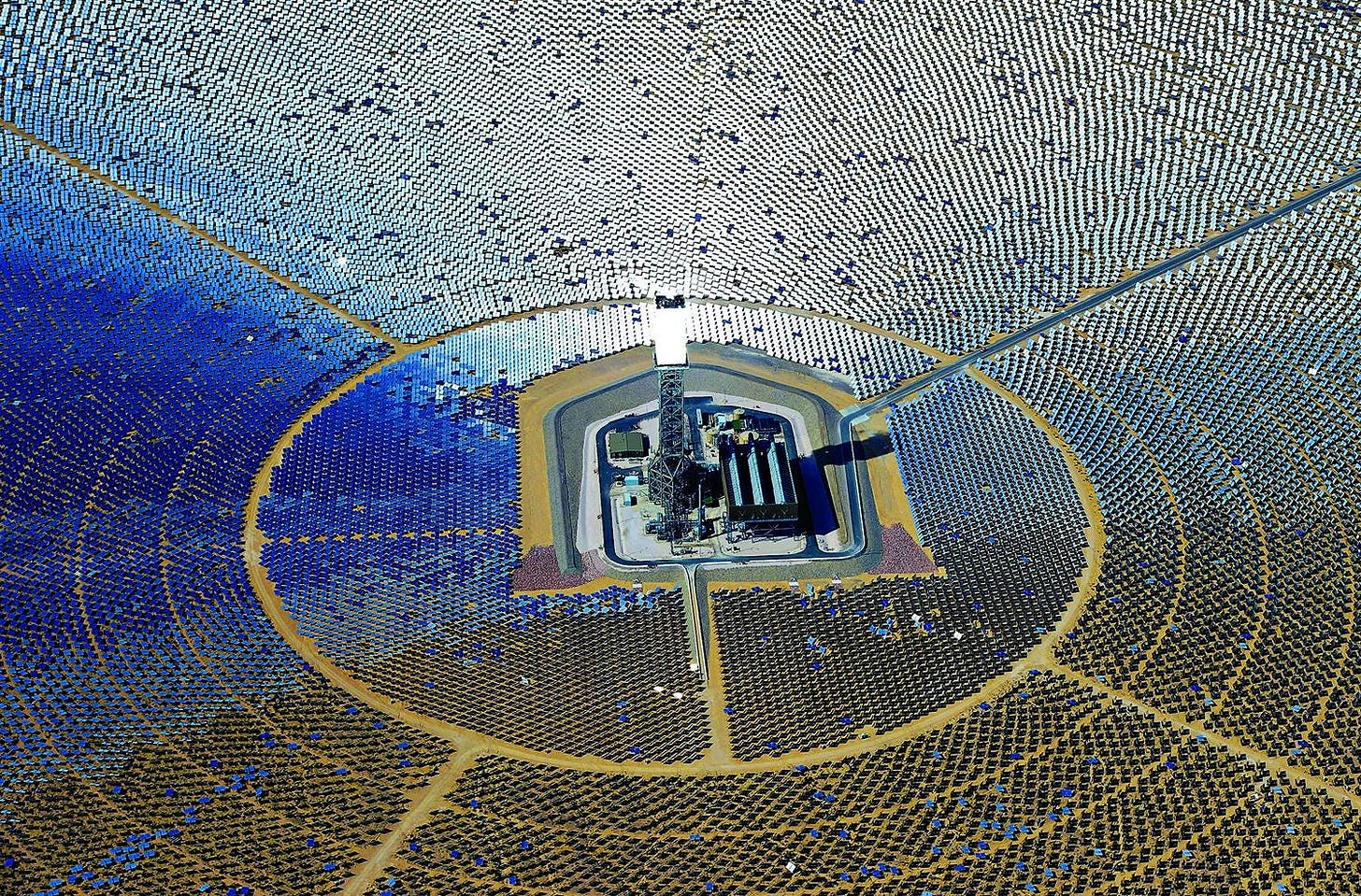

Probably the most important solarpunk development of the decade, though, is that we were right to bet on solar power. The technology could have plateaued. Instead, costs keep dropping. Efficiency keeps improving. Deployment keeps hockey-sticking. Circularity is getting closer. Land use is looking less zero-sum. A lot of this is thanks to China, but everyone is getting a piece of the action. Solar panels are now cheaper per square meter than wooden fencing. We don’t know what The Street is going to do with this tech now that it’s cheap, but I expect we’ll soon find out. Batteries are coming along too——turns out you can make really cheap ones out of salt, no Lithium Wars required. In general the world of renewable energy generation and storage continues to be full of ideas worth sci-fi-geeking out over.

So what’s next? Where does solarpunk go for its next decade?

I think there’s a certain amount of “letting it breathe” that can and should happen. In my own work, I’ve felt drawn to writing solarpunk stories that aren’t didactic or post-normal, aren’t trying to communicate solutions, are just about living in the world that’s emerging, beautiful and terrible. I think there’s going to be a lot of that.

And there’s going to be a lot of solarpunky images and characters and architecture casually showing up in TV and movies and video games and anime, which will then percolate into the real world in various ways. That’s already baked in, the result of our years of labor putting our hands in the cultural soil.

We’ve spent over ten years imagining better futures. When I wrote “Dimensions,” that task itself seemed daunting, obscured as alternatives were by the choking neoliberal smog. But, in a tremendous feat of collective imagination, we did it. We pulled it off. From the policy-wonkish, to the pro-topian, to the perfectly utopian, we’ve created a range of answers to the question, “what does a sustainable world look like?” Solarpunk can now serve as a vital shorthand for that set of imaginaries.

I’m not saying the worldbuilding work is fully complete, but I do think we’ve reached a robust place. It’s time we turned our attention to other tasks, to the other part of the definitional question: “how do we get there from here?”

What’s next needs to be not just narrative and aesthetic interventions but actual interventions, in material reality. Not just future visions but concrete projects and plans——hundred year plans, if you can swing it——working with actual people in actual places. This is a harder sell after a decade of everyone getting more online, but one thing I’ve learned from my students is just how discontent we all are with this shift, just how ready we are for what solarpunk offers.

One of the truly wild things about following this stuff for the last ten years is that the most intensely solarpunk examples all come from real life, not fiction. The solarpunks already exist; their stories just aren’t evenly distributed yet. Cyberpunk didn’t invent the persona of the hacker, but it did make a whole lot of people want to be hackers. Solarpunk can and should do the same, pointing us toward lifestyles, careers, communities, and choices that are regenerative for both the planet and the soul. It shouldn’t just show us a solarpunk world, but show us how to become the solarpunks, right now, who can build it.

Personally, I’m getting older. Saving the planet is going to require digging a lot of ditches and hauling a lot of solar panels up onto roofs and potentially strolling through a lot of tear gas. That’s all a young man’s game. If a global civilian climate corps started recruiting able-bodies tomorrow, I’m not so sure I’d make the cut.

But on the other hand, my parents have, slowly but surely, over years, replaced much of the grass of their suburban lawns with raised beds, fruit trees, grape trellises, berry patches, compost bins, rainwater barrels, edible cover crops, and pollinator-friendly ornamentals. It’s a truly beautiful transformation. If they can do that in their 70s, I can surely find something useful and generative and solarpunk to do in my 40s.

In conclusion, the basic analysis of “Dimensions” still seems right: the neoliberal nation-state may be fucked, but the street, the neighborhood, the town, the network, the people can thrive——and make something better. And the final sentiment of “Dimensions” seems right too, with a few small edits:

I wrote this because I believe the enormity of our problems doesn’t have to paralyze us. Quite the opposite: seeing [how the world could be] is vital if you are going to [make sense of how it is]. Now is the moment to be [re]galvanized, to know that we [have been] on to something, and to make acting on these ideas a real part of our lives.

So I leave you with this provocation: forget what you’ve imagined, and instead ask yourself how will you be a solarpunk? How will you be one this year, this month, this week, tomorrow? There’s no time to waste. The next decade has already begun.

Fellows + Travelers

Longtime solarpunk thinker Jay Springett is bringing his weekly podcast project, 301 Permanently Moved, to a 301-episode conclusion. It’s been a truly impressive project, both as a creative practice (for a long time the challenge to himself was to write, record and edit the podcast in a single hour) and as a sum body of work containing thoughtful commentary on a vast array of subjects in a vast array of forms. I highly recommend checking out the last of the run.

SFF writer Sam J. Miller has a new newsletter/fiction project called Undercover in the Apocalypse, which I’m excited to follow.

Wren James, prolific writer and founder of the Climate Fiction Writer’s League, has put together and released the Climate-Conscious Writers Handbook. It’s sort of one part cli-fi genre primer, one part writing exercise journal and story planning notebook. I contributed a smidge of feedback on the project, so it’s cool to see it live!

Lizzie Wade, author of the freshly released APOCALYPSE: How Catastrophe Transformed Our World and Can Forge New Futures, had a great post about AI and the unfortunate dawn of a new, extractive “imagination economy.” The piece quotes my own recent anti-AI dispatch and feels like an important continuation of the conversation I was writing into.

If you liked this newsletter, consider subscribing or checking out my climate fiction novel Our Shared Storm, which Publisher’s Weekly called “deeply affecting” and “a thoughtful, rigorous exploration of climate action.”

I was chronically ill as fuck in 2014, I'm even more chronically ill as fuck in 2025. I can't say for sure whether I relate to any of this - aside from feeling old & helpless... lol. But I'm still here, reading this - that's something, I guess.