“Pursuant to the Agreement”

How might the United States manage its nuclear waste once the states are no longer united?

Way back in spring of 2024 — feels like ancient history now — I participated in a narrative hack-a-thon put on by my friends at ASU’s Center for Science and the Imagination. The gist of a “narrative hack-a-thon” is that you get a bunch of interesting thinkers together, with various expertise, you team them up with SFF writers, and you have them brainstorm a sci-fi story on a particular topic or question. I’m an old hand at these, having done a couple with CSI on solar energy back in the deep beforetimes of 2018 and Jan. 2020, and then organizing four workshops about the Swedish energy transition with Luleå University of Technology in 2023. Just this week I facilitated a similar workshop on reimagining public goods. This one, however, broke the mold, for it wasn’t about the bright but complex future of renewables, but rather the messy, historically fraught question of what the US should do with its nuclear waste.

I didn’t know a ton about nuclear waste management (NWM) going into this workshop, but thankfully the workshop served as an excellent crash course. The question was about how we might create a consent-based siting process for a hypothetical “temporary storage facility” — basically a warehouse where sealed casks of spent fuel rods could be gathered from where they currently sit at active and decommissioned nuclear plants around the country, to await eventual disposal at an also-hypothetical permanent repository. That’s a lot of jargon and bureaucratic mumbo-jumbo. What it boils down to is: would you say yes to the government storing something potentially scary in or near your community? If you did say yes, did give your ‘consent,’ what would that consent mean? How long would it last? Could that consent be withdrawn or renegotiated by future generations?

My group got interested in that bureaucratic mumbo-jumbo, and we devised a story, told in documents, about trying to keep such a facility going over decades — decades in which America experiences a profound political crisis that sees the breakup of the Union. Back in 2023 this “Great American Fracture” felt like a distant possibility. Today, seeing ICE thugs invade American cities and disputes between state/local governments and federal authorities over everything from tariffs to college curricula to whether it’s wrong to shoot an unarmed civilian in the face, this vision feels all too plausible.

The story I eventually wrote up is titled “Pursuant to the Agreement.” It’s an epistolary story, documents framed as a series of exhibits at a future Museum of the American Fracture. You can now read it in the book Our Radioactive Neighbors, edited by my colleagues Clark Miller, Ruth Wylie, and Joey Eschrich. The volume also includes stories by Justina Ireland, Carter Meland, and my friend and fellow solarpunk Sarena Ulibarri. This fiction is supplemented by about a hundred pages of essays explaining and exploring the mechanics of nuclear power, the history of NWM and siting policy, the complexities of seeking community consent. It’s all extremely thoughtful and informative. If you ever wanted to be able to impress your friends at dinner parties by mastering a grim and arcane but genuinely fascinating topic, well, this book could probably get you most of the way there!

There is also a really nifty supplemental facilitation guide featuring questions and activities that can be used to start conversations about the stories. Part of the role of the book, used in the larger 3CAZ series of community forums, is to help communities develop the imaginative capacities required to make hard collective decisions. Several of us involved in the book discussed all this on Tuesday, at an event capping off the whole 3CAZ project.

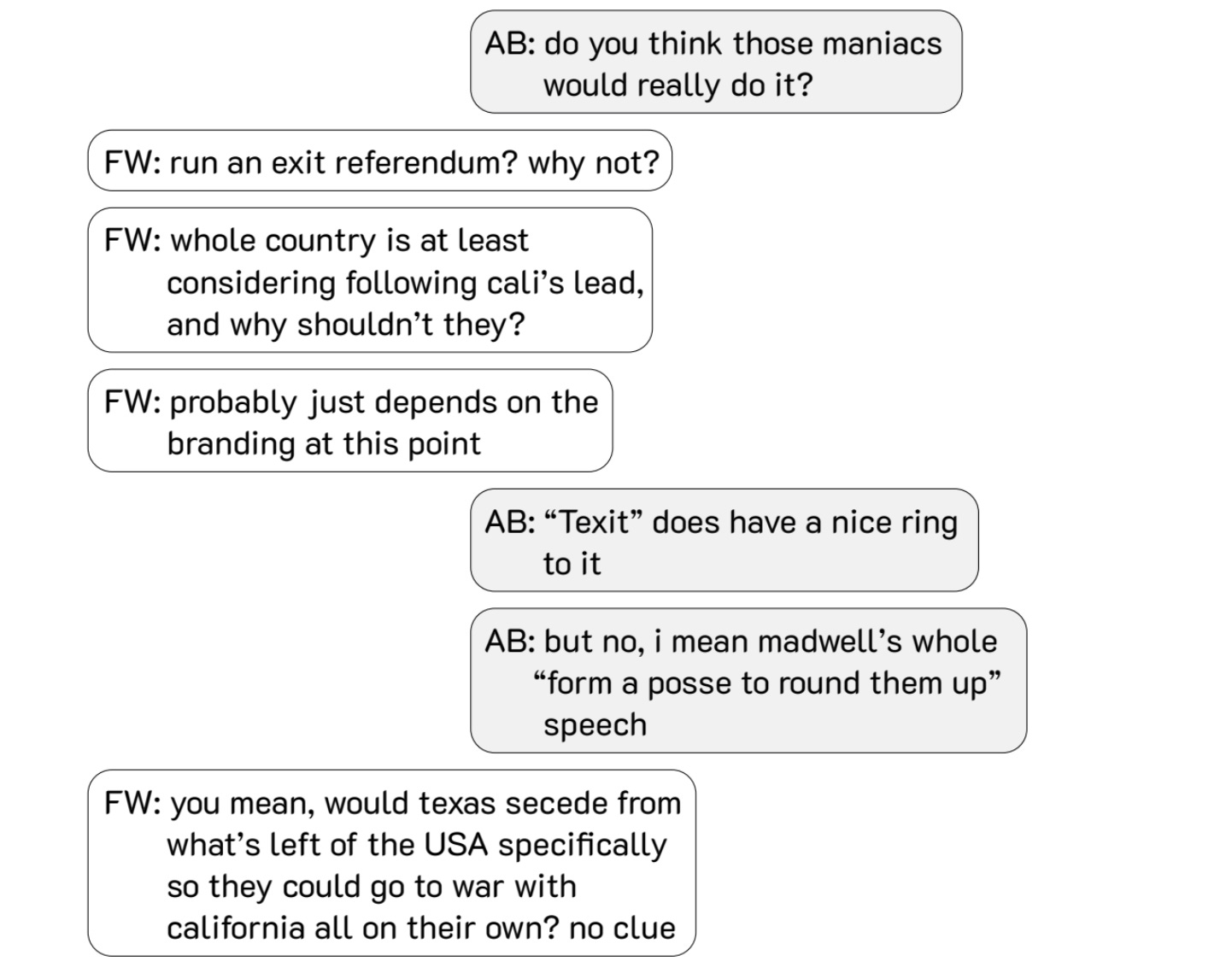

Here’s a snippet from “Pursuant,” from right around the middle of the story:

“Pursuant to the Agreement” sprawls across decades and generations and text genres. It features official documents, diplomatic communiques, text message conversations (see above), meeting transcripts, handwritten letters, and fuck-you emails, all held together with curator’s notes that give a 22nd century perspective on 21st century institutions, expectations, and foibles. It’s about trying to hold together a long-term project across an ever-shifting policy landscape and an ever-swinging political pendulum — in this case one swinging wildly enough to break its moorings and go careening off over the historical unprecedented horizon. Which, you know, relatable.

In the almost two years since we had the workshop, that pendulum swang has resulted in the phrase “consent-based siting” being stripped from some federal web pages. The preferred term now is “collaborative siting.” Apparently the word “consent” is triggering for the various bullies and rapists that set our nation’s agenda these days. There’s also been a notable SCOTUS ruling related to proposed interim storage sites in West Texas and New Mexico. It’s unclear whether an interim storage facility is actually that much closer to being built.

And probably we should build one. After all, none of the communities around where we currently store our spent fuel rods actually consented to that situation. All of them were promised that the waste from their nuclear plants would be moved to a permanent repository by now. It would be good to consolidate all that in-situ waste before the concrete casks get damaged by climate disasters and start leaking radioactive materials into the environment.

In many ways the fundamental issues when it comes to nuclear waste siting are not so different than those in siting carbon removal projects, which I’ve discussed before, or, for that matter, the huge AI data centers the Magnificently Sloppy Seven want to build all over. There are local burdens and histories and injustices to consider, balanced with notions of national or global or economic good. Some of those goods are more convincing or palpable or immediate than others. Same with the burdens. The goods are not always evenly distributed, nor are the burdens. It’s easy to feel like the whole thing is too swamped with nuance and knotted with human feeling to ever Do It Right — if you can even agree on what that means.

I think we’re at a moment when people are waking up to the reality that the future is not a stack of immaterial abstractions. It’s not in the cloud or the metaverse or the bodiless, agreeable text streams of chatbots. Or at least, not just there. Those abstractions must be brought into being by infrastructure in the real, material world, and that infrastructure has costs and complications. It uses energy and water and land, requires roads and labor, makes noise, has ripple effects on the food-energy-water-waste-compute nexus. Same for any material projects we might undertake, such as scrubbing the skies of carbon or burying other sorts of waste in the ground or building housing or high speed rail or yet more strip malls. We can do strange and futuristic things, but those things must be done somewhere, somewhen, and that means involving real people with real, far-from abstract lives.

Check out “Pursuant to the Agreement” and all the stories and essays in Our Radioactive Neighbors: Collaborative Imagination, Community Futures, and Nuclear Siting Practices.

Preorder My Novel

And if you’d like to read more socially complex explorations of speculative political events, Absence: A Novel comes out May 5th! Get it from your local bookshop or preorder it via your preferred online retailer here.

If you don’t want to wait until May, you may be able to get an early look via Netgalley, if you’re a user there. Several readers have already left reviews of the novel at Goodreads, calling it…

“a character-driven, slow-burn speculative mystery with lots of questions and not all the answers”

“a clever story well told”

“one of those books that will leave you guessing until the very end”

“a great read to start the year!”

Art Tour: Becoming the Sea

Was in STL over the holidays and saw an amazing set of site-specific paintings by Anselm Kiefer at the SLAM. Truly pictures do not capture what it feels like to walk up to one of these, but hopefully this gives you some sense. Fiancée for scale.