Where and When (and How Much) to Fix the Climate

reflections on carbon removal and environmental justice

The world is full of plans and prototypes and proposals, but any such that hope to actually impact the living, dying material world must choose a time and a place. The problem is that space is limited — everywhere has been mapped and managed and parceled — while time feels infinite — why not start tomorrow, or next year, next decade or century? And so a great many good ideas fail to achieve takeoff. Or perhaps a better metaphor is they fail to land, unable to find an open runway, circling the airport endlessly, burning fuel.

I spent the last two weeks visiting Washington DC and then Louisiana as part of the Carbon Removal Justice Fellowship organized by the National Wildlife Federation and American University’s Institute for Responsible Carbon Removal (whom I have worked with before). Funding came from the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative before they pivoted away from climate work to philanthropy more politically palatable to the ascendant right. The fellowship brought together an impressive and diverse group of researchers, policy wonks, and activists to consider the intersections between environmental justice (EJ) and carbon dioxide removal (CDR).

Here’s the story as I understand it. For a long time the idea of removing CO2 emissions from the atmosphere was considered a radical, impractical technofix. It was lumped into “geoengineering” with various stratospheric aerosol schemes, albedo manipulation, and space mirrors. It was, most everyone agreed, much better to simply stop emitting than deal with the carbon after we’d already burned it. But years ticked by and climate action was weak or nonexistent, the energy transition proceeded without replacing much fossil energy, and emissions kept going up. Plus, the planet was heating up faster and with more obviously destructive consequences than anticipated. So in 2018 the IPCC included CDR as part of its 1.5 report: things had gotten out of hand enough that if we were going to hit our targets, we didn’t just have to decarbonize, we also had to do some CDR, to the tune of probably tens of millions of tons a year by 2050.

How to do this is still an open question. There are various “nature-based approaches” that seek to improve carbon uptake in the soil, wetlands, and forests through conservation or regenerative farming or plowing carbon biochar into fields. These are often charismatic solutions, with lovely co-benefits for ecosystem health, but are tricky on MRV: Measurement, Reporting, and Verification — basically, knowing/proving that you are actually drawing down carbon and keeping it out of the air. And nature-based sinks can only hold so much. After all, most of the CO2 we’ve dumped in the air was once locked away deep underground as fossil hydrocarbons; there’s just not room to hold all of it in the biosphere unless we want the Earth to look jurassically different.

So pretty much every serious analyst in this space thinks that reaching gigaton scale will require some amount of industrial CDR: using machines to capture CO2 and store it in underground reservoirs or convert it into some durable, inert substance like concrete. There are machines that do this straight from the open air (Direct Air Capture, or DAC), and machines that do “point source” capture at power plants or industrial facilities (commonly and confusingly called Carbon Capture and Storage, or CCS). Burning fossil fuels and capturing the CO2 waste is certainly better than dumping it into the atmosphere, but that doesn’t amount to the “negative emissions” the IPCC says we need to stay under 1.5°C or 2°C warming by 2100. But if you harvest biomass (trees or agricultural waste or even corn ethanol), burn it for energy, capture the CO2, and then regrow the biomass (a process called BECCS), perhaps that can count as a removal? It gets twisty.

There are many such hybrid and edge cases. Like Enhanced Rock Weathering (manipulating certain minerals so that they can more efficiently fix CO2 out of the air), which can look natural or industrial depending on how it’s deployed. Or Ocean Alkalinity Enhancement — dumping stuff in the ocean to change it’s pH, which can help it absorb more CO2. Or maybe we can take biomass waste, grind it up into a slurry, and inject it into the seabed. People are devising many clever and interesting plans/proposals/prototypes.

The point is: after 2018, CDR, in all its myriad industrial and nature-based and hybrid forms, began to be taken very seriously. Some countries started talking about funding mechanisms, and some companies like Microsoft started buying carbon credits to balance out their emissions. Some demonstration projects came online.

Hitting that gigaton-scale goal, however, would mean building out a whole new industry, one the size of, say, the automotive sector. One startling figure I heard last week was that CDR could become the largest industry in the world by volume of material moved — CO2 pumped through pipelines, ERW gravel trucked to fields, biomass shipped for storage or burning, etc.

That’s a big industry! How we pay for it is one question. CDR isn’t a commodity like electricity that one might buy and put to use; it’s global public good that transcends borders. So it’ll probably have to be paid for by nation-states or other public entities, or by state-enforced mechanisms that wrest funds from the fossil majors as payment for their climate crimes.

Another question that loomed large in those first couple years after 2018 was who would reap the benefits of all the economic activity CDR promised to create. Who would own the firms that did CDR? Which communities would get the jobs and investment? Would this be another case of the rich cashing in while the poor are excluded from the boom? In 2022 I myself wrote a story in which wealthy white suburbanites in Reno could “pull money out of the air” with backyard DAC rigs, to the consternation of poorer Latino folks who lacked the capital to keep up.

There was a strong feeling in some progressive circles that CDR was a chance to “do industry right,” directing the money and opportunity created by this promised carbon boom to the very communities harmed by the petrochemical industry or disadvantaged by racialized capitalism more generally.

So when, in 2021 and 2022, the Biden Administration began to craft the landmark climate legislation that would become the Inflation Reduction Act (RIP), not only did they direct billions of dollars toward scaling the CDR industry (largely through a mechanism called the 45Q tax credit), they included CDR in the “Justice40 Initiative.”

Justice40 was a plan, now in tatters under the Trump administration, to direct 40% of certain federal investments to benefit disadvantaged communities, particularly those “frontline” areas impacted by pollution and hazards, known in the environmental justice movement as “EJ Communities.”

Environmental justice is very focused on preventing and rectifying localized environmental harms, which have historically been disproportionately inflicted on Black, brown, Indigenous, and poor communities. EJ is not the same as CJ (climate justice), though the latter was born out of the former. The provision of global climate stability might thus seem far afield from EJ concerns, but nonetheless there was a reparative and redistributive EJ vision at the heart of the Biden CDR policy.

What has become apparent in the years since the IRA passed, however, was that this policy fundamentally miscalculated. EJ activists and people in EJ communities looked at the CDR projects being proposed for their areas and saw huge industrial structures that looked suspiciously like petrochemical infrastructure. They saw the deployment of this emerging tech near their homes not as a reparative gift, but as a kind of experiment that would never be run on wealthy white suburbs. And they saw the startups and industry players pouncing on federal CDR money as more of the same: landmen out to secure permits with promises of jobs and limp community benefits that would fail to bring real prosperity and might not be worth the risks and tradeoffs even if they did. The message that was sent back to CDR advocates was “don’t do this here.”

This was the animating impulse behind the fellowship I’ve just completed: trying to square the circle between EJ’s cautionary, preventative, and community engagement/benefit concerns, and CDR’s redistributive and climate opportunities. We need to get carbon out of the planet’s air and put it back in the ground, but where, specifically, should that happen? We need to act on climate as fast as possible, but how to balance that urgency with taking time to make sure plans are safe and communities feel both informed and heard?

We met with federal policymakers on Capitol Hill and state reps in Louisiana, plus nonprofit think tank wonks, academic researchers, PR operatives from CDR companies, and others. We had long and sometimes emotionally difficult discussions. In the end I left with a weighty, anxious sense that this whole endeavor was turning out to be slower, messier, and more complicated than any of us had hoped — and that even before Trump and co blew up the IRA and all US climate policy/science.

How accurate is the EJ perception that CDR = new oil and gas? I don’t know. There are certainly aesthetic and technical similarities between some industrial CDR approaches and petrochemical plants and pipelines. But the risks from, say, a DAC facility seem to me an order of magnitude less severe than, say, an oil refinery. There just aren’t the same nasty byproducts or combustive reactions in the mix, and the whole point is to clean up a form of pollution. CO2 is a largely inert molecule compared to the volatile hydrocarbons of petrochemistry.

Not to say it’s harmless. In 2020 a landslide ruptured a poorly constructed CO2 pipeline near Satartia, Mississippi. The resulting leak swiftly and invisibly knocked people unconscious. The town of 200 had to evacuate and 45 people ended up in the hospital with CO2 poisoning, some of whom have experienced long-term health effects. This incident looms large over the whole industrial CDR sector.

And then there’s the reality that not all “carbon management” projects cashing in on the 45Q tax credit are in the business of scrubbing the air. One Louisiana project we learned about in depth was a plant proposed by a company called Air Products, which would use use methane to make hydrogen and ammonia, but would capture the resulting CO2 waste and pump it into a pore space under Lake Maurepas — thus producing low-carbon fertilizer and “blue” hydrogen. This seems much more like a traditional petrochemical plant in its risks and impacts. And in the long run, the world is certainly going to need a lot of low-carbon fertilizer, but it’s very unclear whether opening this facility would actually speed the closure of some equivalent carbon-intensive hydrogen/ammonia facility. I didn’t come away feeling very enthused about this particular carbon management project.

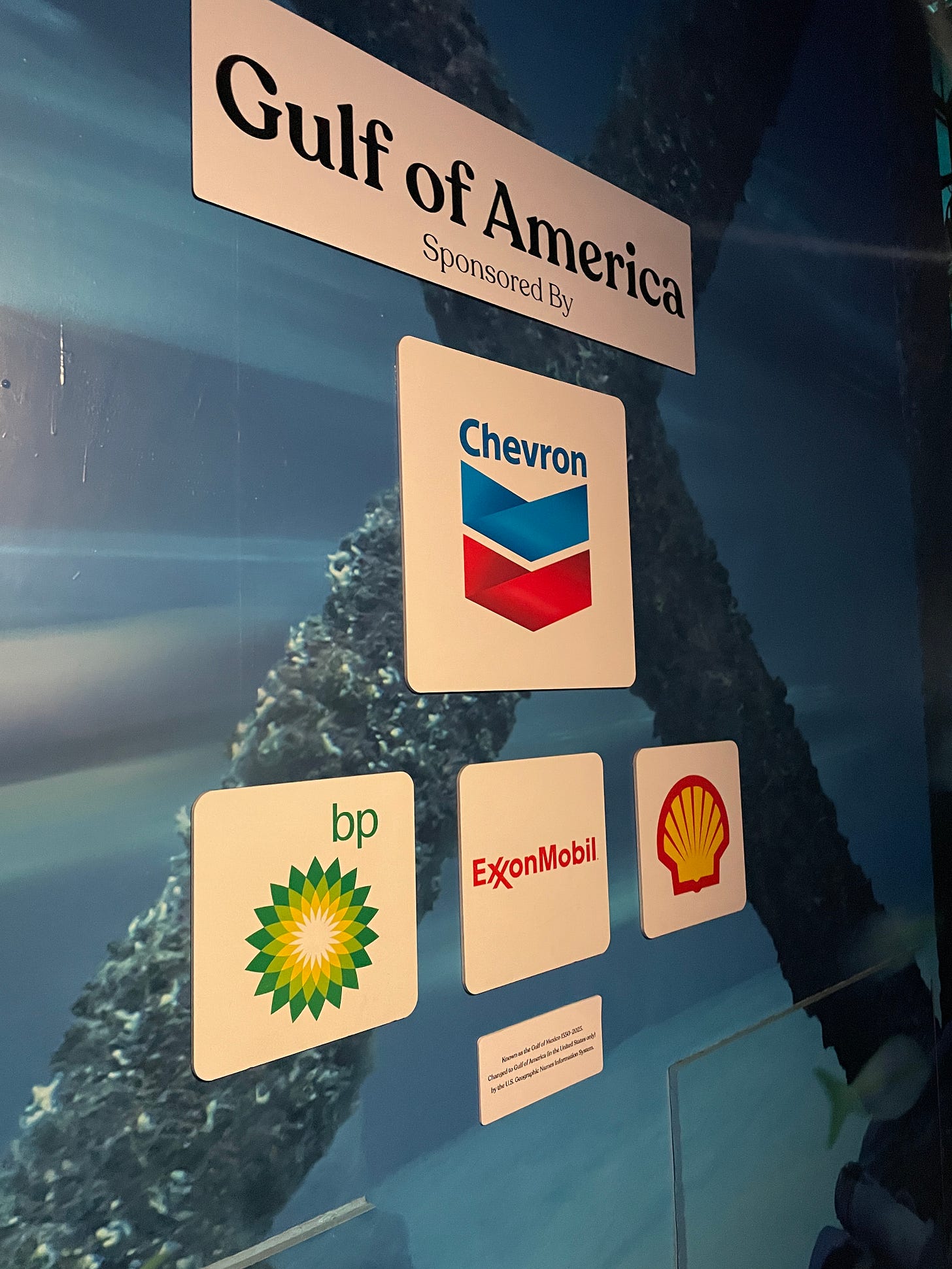

It doesn’t help perception that the fossil fuel industry is a big — probably the biggest — player in the CDR space. And often they talk about CDR and particularly CCS as a way to keep their toxic business going for further, deadly decades. They even want to use captured carbon to flush more hydrocarbons out of spent wells, a process called enhanced oil recovery (EOR). That’s bad! Lots of us have written about the need to keep the fossil fuel industry out of the CDR space, but so far that hasn’t happened. They’ve slithered their way in and bought up CDR startups and technologies and dismantled policy attempts to exclude petro-friendly methods like CCS and EOR. It’s a disappointing, if predictable, turn of events, and one that validates critics who view CDR as a false solution propping up the fossil fuel industry.

On the other hand, the fossil fuel industry does have a lot of tech and expertise that’s useful for doing CDR. Presumably a just transition would give oil and gas workers who might be hurt by the shutdown of their industry the chance to put their skills to better use on CDR projects. Similarly, there are real material reasons beyond the Justice40 policy why CDR might be sited near pollution-impacted communities. The geology that made Louisiana so plump for fossil fuel extraction also makes it full of potential for Class VI Wells, which CO2 must be sequestered in to claim that 45Q tax credit. And communities around petrochemical infrastructure may already have workforce with the skills needed for CDR projects.

On the other other hand, perhaps the fossil fuel influence is limiting our imagination. Why capture carbon in one place and then send it via pipeline to a disposal site? Why not do the DAC right on top of the storage reservoirs, powered by on-site solar and wind?1 Why not site such facilities in the remotest areas, as far away from people as possible? Why not make them autonomous, just sucking and pumping, monitored by a skeleton crew of maintenance engineers who hike out for months-long tours like those solitary souls living in firewatch towers, or that couple in The Gorge (2025)?

There are practical difficulties with such a vision. For one, it’s hard to sell such a project as a source of jobs, which is how we’ve gotten used to pitching climate infrastructure, perhaps to our long-term detriment. For two, it’s hard to build things far away from housing, services, et al. But it’s not impossible, and I suspect it will get more and more possible as solar unlocks truly decentralized energy access.

Anyway, EJ activists argue that the concerns of frontline communities should not be conflated with the NIMBYism of affluent “fenceline” communities. Certainly many EJ communities are historically justified in their suspicion of industry and government people telling them not to worry about that pipeline by the school, that smokestack plume, that murky tap water. But in Louisiana, I found it hard to tell how much opposition to CDR was based on EJ concerns and how much was motivated by NIMBYism or viral misinformation or even climate denial.

If you don’t acknowledge climate change — and many people in Louisiana, rich and poor, don’t — the whole concept of putting carbon back in the ground rather than venting it into the air makes no sense. We heard of people opposing projects from a purely “why do we even need to do this?” perspective. We heard of people snubbing CDR startups because they wanted to hold out for a better deal from a richer oil and gas company. We heard of conspiracy theories about solar panels leeching chemicals into the water supply.

Despite or perhaps because of the contradictions, I think most of the fellows came away from these past two weeks feeling like CDR should just not be sited anywhere near EJ communities. As well intentioned as Justice40 was, the reality is just too fraught. They don’t want it, EJ activists have warned, and they shouldn’t be made to do the work of coming around to it. I’m sympathetic to all of this.

But I also came away feeling like there is a deep lack of clarity in the carbon removal space around scope. We have the gigaton number to shoot for, but beyond that, just how much carbon are we talking to about drawing down, and when?

I’ve written before about thinking of climate action as falling into a few distinct “civilizational projects”:

Decarbonization: transitioning the energy system, shutting down emissions, stabilizing the climate so we stop getting warmer.

Climate Repair: cleaning up the carbon in the atmosphere so we can cool the planet back to a more habitable temperature.

Planetary Management: keeping a hand on the “global thermostat” into the long term, optimizing the temperature and dealing with any disturbances in that equilibrium.

Similarly, we can break down CDR into categories:

Residual Emissions: greenhouse emissions that have proved too hard to abate, and thus should be balanced out with CDR. There’s a whole politics around what should count as “hard to abate.”2 This is the CDR you care about if your goal is being “Net Zero.”

Overshoot Emissions: emissions that push us past our climate goals. We are about at that 1.5°C threshold, so any additional emissions should be drawn down if we want to hit our 2100 targets. This is the CDR you care about if you goal is to stabilize the climate at that 1.5°C or 2°C marker.

Legacy Emissions: all the past emissions since the beginning of industrialization that have pushed warming as far as it’s already gone. Do countries or companies have a responsibility not just to get carbon neutral, but to clean up their carbon waste? And do we really want to live on a 2°C hothouse Earth indefinitely, or would we prefer to lower the temp back to holocene levels? This is the CDR you care about if you want to do climate repair to cool the planet back down under the stabilization point.

Fluxes: CDR done after the climate repair project is complete as part of a larger planetary management project, balancing the earth system over the long term.

I think a lot of the tensions in the CDR space, particularly when it comes to EJ issues, flow partly from and into unarticulated differences over the importance of these different categories.

If you think industrial carbon removal is inherently an endeavor that puts communities at risk and damages local environments — that every facility is a Satartia waiting to happen — then it makes sense that you would want to minimize the CDR buildout. Climate repair is not a project that should be countenanced. CDR should be allowed only for the very hardest to abate residuals, and perhaps even those shameful emissions could be decarbonized in time. Then the CDR industry could be shut down and consigned to history with the rest of the fossil era. And indeed, I heard one fellow inquire whether CDR facilities would shut down once decarbonization is complete.

Similarly, perhaps you are suspicious that every ton of carbon removal is just a license, moral and sometimes literal, to emit more carbon. In that case, if some locals say are resistant to a particular project, then why push the matter? No reason to allow any more of this ‘false solution’ than we have to, particularly if there are reasonable objections on the ground.

But if you think climate repair is necessary, for the atmosphere is already too hot and dangerous, then perhaps you see CDR differently. You may be looking toward an industry orders of magnitude larger.3 Which means, probably, that more projects need to work out. One can still be critical of CDR companies and how they engage with communities, but I think it’s harder to feel good about a slow and stymied build out if we have so far to go. In which case, it makes sense to put more effort into resolving the concerns and difficulties and contradictions CDR projects raise.

I think it would be supremely helpful if everyone involved in conversations about CDR siting could just say, out loud, which emissions they care about. Otherwise, we’ll all just keep talking past each other, each side unclear on why the other is so reticent or, alternatively, so eager. We’ll never be able to agree on where or when to do carbon removal if we can’t talk clearly about “how much.”

Now, you could also argue that all this is jumping the gun; that we shouldn’t really be considering a multi-gigaton scale CDR sector until we have a fully renewable energy supply; that it’s up to future people if/how/where/when they choose set the global thermostat. And that’s fair. All this is just barely past nascent.

But I think it’s likely that future people will feel themselves trapped in path determinacy by our choices today, just like we feel trapped by the systems built by preceding generations. If we dream big now, and work to do hard, tricky things for the sake of centuries we will never see, we may actually be remembered as good ancestors.

I truly do sympathize with the communities who feel threatened by CDR projects in their backyards or under their lakes, or who want better deals than that old oil and gas bribe of a playground and a few tenuous jobs. But at the same time, CDR seems to me inherently different from the extractive, poisonous petrochemical industry. What’s the opposite of a moral injury? CDR gives communities a way to be a part of a grand civilizational effort to fix the climate — a chance to be climate heroes!

So consider this a clarion call to all CDR-YIMBYs. Make yourselves known! Get loud and demand robust negative emissions in your backyard! Help your neighbors understand the local risks and the enormous planetary benefits.

Truly, we need you. These last few weeks have driven home that all good ideas can be stalled and stymied by the devil’s details: Where to do it? When to do it? How ambitious are we willing to be?

Personally, I say more ambitious. I want future generations to taste that crisp, sweet holocene air. If it means putting a DAC rig in my back yard, so be it.

Recommendations + Fellow Travelers

Shout out to Patrick Tanguay for featuring my Solarpunk 10 Year Retrospective in his excellent Sentiers newsletter. Sentiers is really one of the best futures thinking roundups out there, and Patrick has promised me he’s going to make it even more solarpunk…

D.A. Xiaolin Spires’ solarpunk story “Luminous Glass, Vibrant Seeds” — which we workshopped last year in an online class I taught — is going to be included in the anthology The Year's Top Hard Science Fiction Stories 9.

Clarion classmate Jenny D Williams has started a newsletter of speculative microfictions titled Certain Impossible Things.

Workshop friend Penny Walker has a story out in the new journal Sine Qua Non.

Author and projection activist A. E. Marling has a dope new self-published solarpunk novel out, Neon Riders.

An ASU classmate of mine, Marrilyn Galvan, has an interesting post published by the NORRAG Global Education Centre in Geneva.

Art Tour: Painting

In DC I visited the Hirshhorn, the Smithsonian’s modern and contemporary art museum. This textured piece reminded me of the mess we’ve made in the air, and our obligation to clean it up.

I’m continually annoyed that the CDR sector seems unwilling to see their tech for what it is: a great way use surplus afternoon electrons in a photon-powered future. But the way these projects are currently financed, you could never pay off your capex loans if you only ran your rig for 3 hours a day. An acute case of fiscal myopia.

Industrial processes like steel or concrete manufacturing might count as “hard to abate,” though there are already lots of ideas on how those could be at least partly decarbonized. So might aviation, as batteries still seem like they may be too heavy to allow for electrification of long distance commercial flights. Though, again, I’m hopeful that these are problems we can solve.

Exactly how big will depend on how long you want the repair project to take. If you’re willing to roll back warming over centuries, perhaps you need to remove only a few gigatons a year. If you’d like to see the job done in decades, then you may be talking about considerably more.

Thanks for the reflections! On math calculating amounts, https://firstgigawattdown.substack.com digs in. I can't align with the author's embrace of nuclear as a primary power form to build out in order to decarbonize, but she does usefully bring attention to setting CO2 removal goals by calculating emissions in a given location.

Yes, a pre-condition for effective action is stakeholders agreeing on definition of the problem. This is where a Citizens' Jury model comes to mind, the essential component of holding briefing sessions upfront with "subject matter experts" to assist the participants in gaining shared understanding of the factors to consider for the topic they're deciding about. How can subject matter experts on CCR be part of making the case for decisions about adoption of this tech?